Model registers “surprise” when objects in a scene do something unexpected, which could be used to build smarter AI.

Rob Matheson | MIT News Office

Humans have an early understanding of the laws of physical reality. Infants, for instance, hold expectations for how objects should move and interact with each other, and will show surprise when they do something unexpected, such as disappearing in a sleight-of-hand magic trick.

Now MIT researchers have designed a model that demonstrates an understanding of some basic “intuitive physics” about how objects should behave. The model could be used to help build smarter artificial intelligence and, in turn, provide information to help scientists understand infant cognition.

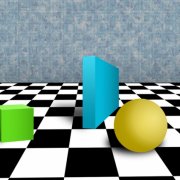

The model, called ADEPT, observes objects moving around a scene and makes predictions about how the objects should behave, based on their underlying physics. While tracking the objects, the model outputs a signal at each video frame that correlates to a level of “surprise” — the bigger the signal, the greater the surprise. If an object ever dramatically mismatches the model’s predictions — by, say, vanishing or teleporting across a scene — its surprise levels will spike.

In response to videos showing objects moving in physically plausible and implausible ways, the model registered levels of surprise that matched levels reported by humans who had watched the same videos.

“By the time infants are 3 months old, they have some notion that objects don’t wink in and out of existence, and can’t move through each other or teleport,” says first author Kevin A. Smith, a research scientist in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS) and a member of the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines (CBMM). “We wanted to capture and formalize that knowledge to build infant cognition into artificial-intelligence agents. We’re now getting near human-like in the way models can pick apart basic implausible or plausible scenes...”

Read the full story on the MIT News website using the link below.